Superfund Sites Reborn

Post-cleanup, Superfund sites across Colorado are finding new life through redevelopment

Eric Peterson //April 30, 2018//

Superfund Sites Reborn

Post-cleanup, Superfund sites across Colorado are finding new life through redevelopment

Eric Peterson //April 30, 2018//

In the 1880s, there were 2,200 mines on the east side of Leadville,” says Greg Labbe, mayor of the historic town in the heart of the Colorado Rockies.

Population peaked around 50,000 in the late 1800s; it’s 2,600 now. “It was madness,” Labbe says. “We glorify that as an age of riches, and it was certainly that, but it was also a time of misery and death and lawlessness.”

And it left a legacy of environmental tarnishment.

The California Gulch Superfund Site in and around Leadville encompasses a dozen different units, including a contaminated railyard just north of downtown. The Environmental Protection Agency declared it a Superfund site in 1983 and embarked on a cleanup effort.

With remediation in its final stages, a new era is dawning on the old railyard. High Country Developers is planning to build 285 housing units over the next 10 years on 39 acres. The look and layout are in the mold of “New Urbanism” communities like Peak One in Frisco and Wellington in Breckenridge.

California Gulch is just one of several Superfund sites in Colorado in the process of redevelopment.

Established in 1980, the federal Superfund program has placed more than 1,300 sites on its National Priorities List, including 26 in Colorado, making them targets for long-term remedial action. The EPA places a high priority on land revitalization, and works with local governments and private stakeholders to help facilitate redevelopment.

Frances Costanzi, coordinator of the Superfund Redevelopment Initiative for EPA’s Region 8, which includes Colorado, points to California Gulch as one of the state’s Superfund success stories.

“Some redevelopment activities include an urban development project at an old railyard, a community sports complex, a nationally recognized multi-use paved trail called the Mineral Belt Trail, and recreational trails along the Arkansas River,” Costanzi says. “In 2014, after decades of cleanup which benefited the ecology of the watershed, the Arkansas River was designated Gold Medal Waters by the Colorado Parks and Wildlife.”

Another success story is on the north side of Denver: the Rocky Mountain Arsenal.

“In the early 1980s, the manufacturing area of this former private and military facility was described as the most polluted square mile in America,” Costanzi says. “Today, the site is transformed into a valuable National Wildlife Refuge and a community asset.”

No two Superfund sites are exactly alike. “Each site seems to bring its own unique challenges,” she adds. “That being said, many of the Superfund sites in Colorado are former mining and/or mineral processing sites, and the size of these sites adds to the challenge. Sites where residential cleanups are needed are also challenging. It takes a level of thoughtfulness and care to work with individual residents to clean up their property.”

Doug Jamison leads the remediation program for the materials and hazardous waste division of the Superfund and brownfield unit at the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment. “Reuse is really one of the main goals of Superfund,” he says. The end goal is to make these properties available for commercial reuse.

“The old real estate maxim applies:

Legendary Denver developer and preservationist Dana Crawford says many Superfund sites “are strategically located for redevelopment.” As a housing crunch pushes land values up, she notes, projects formerly deemed unworthy of risk suddenly pencil out as profitable.

One such project is in Denver city limits, the Shattuck Chemical Co.’s former facility just two blocks west of Broadway in the Overland neighborhood on the south end of town. A concrete monolith meant to contain the radium-processing remnants of the plant was discovered to be leaky in the late 1990s and a cleanup commenced. For seven years, workers jackhammered the monolith and loaded the radioactive rubble onto Idaho-bound railcars.

Soaring real estate values in Denver recently made the 5.8-acre property, part of the multi-unit Denver Radium Superfund Site, a prime site for mixed-use development.

And that’s exactly what’s happening: Dallas-based Encore Enterprises broke ground on a 224-unit apartment complex on the site in early 2017, with the first occupants slated to move in by early 2018.

“I think it’s a huge win for the community,” says Jolon Clark, who represents Overland on Denver City Council. “It makes me happy to see that property redeveloped.”

Once a big void in the urban fabric, the Shattuck site will soon be an economic engine for Denver. “There are a couple of projects over there that have been talked about that could be catalyzed,” Clark says. “This is the first step.”

About 100 miles west at the Eagle Mine Superfund Site near Minturn, the page has turned on a vision for a luxury development complete with private ski slopes proposed a decade ago by Florida developer Bobby Ginn. “We’ve been looking to downsize it a bit,” says Tim McGuire, director of development for Crave Community Co. in Minturn. “We’re focusing on the property closer to Minturn and we want to build market-rate housing on it.”

About 700 units on 500 acres will range from affordable rentals to $1 million single-family homes The 4,600 acres on Battle Mountain above the Crave project — that were going to include the ski lifts in the previous plan — are on the market for $19.5 million.

The EPA recently published a Record of Decision on the site, clearing the way for redevelopment. That, and the newly approved zoning change paves the way for construction after the EPA approves final designs. “It’s a significant moment for us,” McGuire says.

“There’s a housing crunch here,” he adds. “To be honest, the big multi-million-dollar homes that were originally envisioned, that market doesn’t seem to be as strong as it was.”

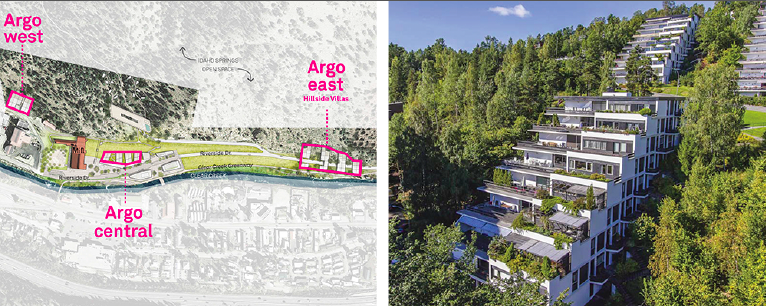

And that housing squeeze is constricting local economies all over Colorado’s ski country. In Idaho Springs, preservationist Crawford is teaming with Mary Jane Loevlie and other partners to redevelop the historic Argo Mill & Tunnel as a mixed-use community with a 160-room hotel and as many as 200 housing units along Clear Creek.

The ambitious project will cost about $75 million over the next five years, and leave the mill intact as a tourist attraction. Construction on the first phase could begin as soon as summer 2018.

The seven-story Argo Mill was the industrial powerhouse used to process ore from the gold mines in the area, located at the terminus of the Argo Tunnel. “The whole thing is designated a Superfund site, but the tunnel is the reason,” Loevlie says.

Ongoing tours here allow visitors to wander the first 200 feet of the 4.2-mile tunnel, the longest in the world when it was completed in 1903. The tunnel served as a transportation route for ore and miners and drained the mines in the mountains between Idaho Springs and Central City.

In 2015, Loevlie struck a deal with the previous owner, Jim Maxwell, and bought the mill and surrounding 27 acres with Crawford and other partners. The EPA owns a portion of the land and operates a water filtration system that removes pollutants from the tunnel’s drainage.

Loevlie’s enthusiasm for the project is contagious. “We’re not like Breck or Vail,” she says of the design. “We’re going to be Victorian industrial — steampunk-y! It’s industrial revolution. I feel like I’m in an H.G. Wells movie when I come in.”

“Mary Jane Loevlie is a very determined woman,” Crawford says. “Year after year, she would invite me up.” Crawford relented and took a look at the property in 2015. She saw the potential for the project immediately.

Loevlie grew up in Idaho Springs and remembers bumper-to-bumper tourist traffic before I-70 was completed in the 1960s “I-70 really killed Idaho Springs,” Loevlie says. “They took over a quarter of our town.”

The interstate wasn’t subject to the soon-to-pass National Historic Preservation Act; that was the case in the later stretch of I-70 in Georgetown. And the economy suffered without the traffic on the main drag.

Loevlie, who got involved in historic preservation in Idaho Springs in 2001, saw a unique opportunity to balance remediation and revitalization with the Argo project. “The housing demand is crazy up here,” Loevlie says. “For so many years, nobody knew we existed. Now it’s the millennials saying, ‘What a cool place.’

“We could be another Gold King,” Loevlie says, referencing the mine near Silverton that released heavy metals into the Animas River after a 2015 flood and was subsequently designated a Superfund site. “Our goal is to make this a poster child for the redevelopment of Superfund sites.”

Crawford agrees, but notes that the bar is pretty high. “It’s been done all over the United States,” she says. Crawford says there’s a wild card: “A lot of the emphasis on the environment under the Trump administration had been eradicated and nobody knows what to expect.”

The CDPHE’s Jamison says future redevelopment possibilities are “a mishmash,” noting that old mines are often unsuitable for residential uses.

Renewable development at Superfund sites is generally difficult. “Economics tend to drive those projects, and the available subsidies,” Jamison says. “These are complicated deals to put together.”

Heritage tourism has proven a better fit at Summitville. “In the summer, we get a ton of traffic,” he says.

Jamison says successes typically hinge on good old-fashioned networking and collaboration. “You’ve got to forge relationships, you’ve got to build partnerships, and you’ve got to work to make it happen.”