Tech startup: Big Mountain Robotics

Eric Peterson //August 8, 2013//

Company: Big Mountain Robotics

Company: Big Mountain Robotics

INITIAL LIGHT BULB IT consultant Jon-Pierre Stoermer helped build a flying machine in 2011, then joined forces with his father, Pierre, to launch Big Mountain Robotics the following year.

“Jon-Pierre was involved in building a quadcopter in kahoots with some folks in the Boulder area,” says Pierre, a retired aerospace engineer. From the experience, the father-son duo saw the potential for unmanned aerial vehicles – also known as drones – in capturing bird’s-eye imagery.

Recognizing the major market desire to process the imagery into coherent mosaics and maps, the twosome developed their DroneMapper software during the first three quarters of 2012.

After launching last October, the Stoermers relocated the company to Delta on the Western Slope in March of this year. “It’s God’s country,” says Pierre of his place at the foot of Grand Mesa. He serves as Big Mountain’s CEO, and Jon-Pierre is CTO.

IN A NUTSHELL “We’re serving various applications where they want high-resolution, real-time images, because things change quickly,” says Pierre.

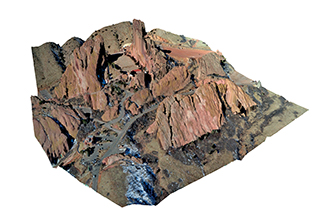

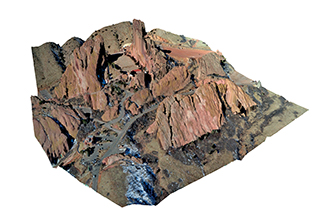

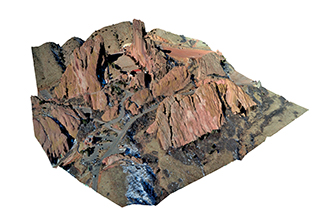

DroneMapper processes image files uploaded by clients into orthomosaics, DEMs and 3D point clouds that allow for a better grasp on the mapped area.

DroneMapper can take aerial pictures to the next level for a fraction of the competitions’ cost. “You can identify crop stress,” says Pierre of agriculture uses. “You come up with a map that’s color-scaled from -1 to +1 – it’s a measure of green-ness if you will,” he says.

3D point clouds “help clients visualize what’s going on terrain-wise,” he adds. Such maps can be accurate to a few centimeters.

And the savings can be significant. Drones can cost as little as $1,000, $200 point-and-shoot cameras offer an accuracy to 15 centimeters, and DroneMapper’s processing runs $20 to $60 per square mile. Manned flights start at $300 an hour and satellite imagery can easily run into the six digits. Add a 5 percent increase in crop yield to the savings over traditional manned-flights or satellite imagery and farmers have the potential to save “serious money,” says Pierre.

The big hurdle: The Federal Aviation Administration effectively bans UAVs in U.S. airspace by mandating a ceiling of 400 feet. “Once the FAA gets its act together, you’re going to see a multitude of new opportunities,” says Pierre, forecasting policy changes by the end of this decade.

State and municipal organizations can apply for waivers to the policy. That’s how Utah uses drones to map ranchland and wildlife habitats.

DroneMapper has been “a gold mine for us,” says Mark Quilter, project manager at the State of Utah Department of Agriculture and Food. “There’s tremendous savings compared to doing it in-house.”

Quilter says the turnaround time of overnight to a week is “amazing,” and the quality of the resulting maps is extremely high. “DroneMapper is able to bring the minute details out,” he says.

.THE MARKET The market for DroneMapper spans oil and gas, agriculture, urban corridor planning and other uses. The FAA policy has not proved to be a roadblock to growth because about 90 percent of sales are in overseas markets, Pierre says.

FINANCING The Stoermers self-funded the company’s launch, but an outside investment might be in the company’s future. “We’ve had a couple calls from VCs fishing around,” says Pierre, who says a cash infusion would help Big Mountain Robotics begin offering end-to-end services as a UAV operator.

where Delta | FOUNDED 2012 | web www.dronemapper.com

“There are potential applications in Greenland to look at the glaciers and the gorges and how they’ve changed over time. That data doesn’t exist now.”

— Big Mountain Robotics CEO Jon-Pierre Stoermer