Denver’s soul food scholar cranks up the heat with ‘Black Smoke’

Meet Adrian E. Miller, culinary historian and food writer

Jamie Siebrase //October 6, 2020//

Denver’s soul food scholar cranks up the heat with ‘Black Smoke’

Meet Adrian E. Miller, culinary historian and food writer

Jamie Siebrase //October 6, 2020//

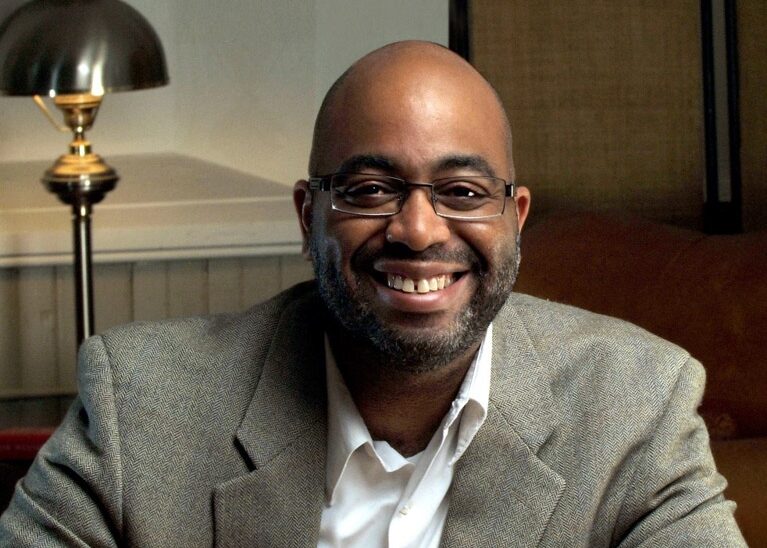

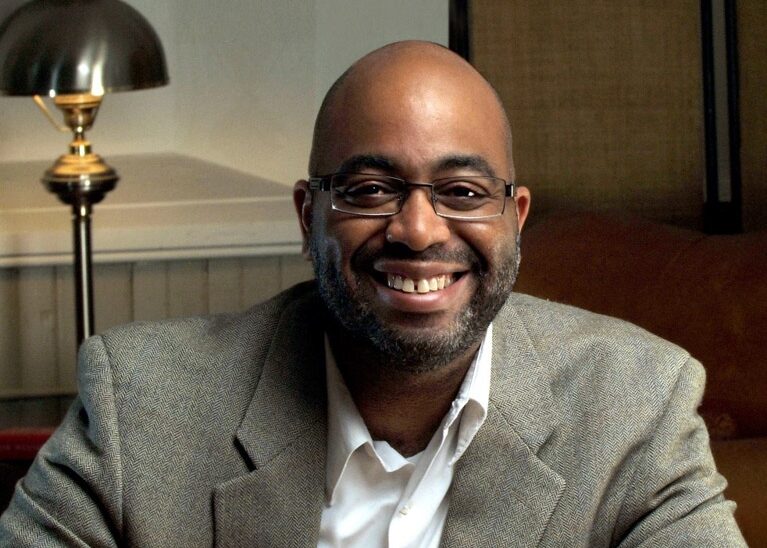

Adrian E. Miller, 51

Culinary historian and food writer

Hometown: Denver, Colorado

Website: adrianemiller.com

What he’s reading: Nothing right now. He’s putting the finishing touches on his third book, Black Smoke: African Americans and the United States of Barbecue, coming spring 2021 through the University of North Carolina Press. The last book Adrian read was The Culinarians.

James Beard Award-winning food historian Adrian E. Miller built a career by breaking from convention … three careers, actually.

The Denver native earned his bachelor’s degree at Stanford University before graduating from Georgetown Law. After briefly practicing law at two prominent Denver firms, he pivoted into politics. Now he’s into his third career as an author and the nation’s premier soul food scholar. He’s also a certified barbecue judge who has lectured across the country on such topics as Black chefs, chicken and waffles, kosher soul food and soda pop. Adrian’s latest book covers the culinary contributions Black people have made to American barbecue.

ColoradoBiz: First things first: Texas, Kansas City, or Memphis? What’s your favorite regional barbecue style?

Adrian E. Miller: I’m a Kansas City devotee. Spare ribs are my touchstone for good barbecue. Growing up in Denver, Kansas City and Texas were the strongest influences. But one thing to understand — when people say Texas barbecue they’re being imprecise. Within Texas there are at least three traditions: Central, Southern and East. In Southern Texas you have a Latinx tradition of Baracoa, whereas East Texas is an African-American style with brisket, usually chopped, with spare ribs, hot link sausage, beef links, boudain, and soul food and creole side dishes.

CB: After graduating from Georgetown Law, you landed jobs at Holme Roberts & Owen, which combined with Bryan Cave Leighton Paisner, and then Dewey & LeBoeuf. Most law school grads vie for jobs at top Denver firms, but you gave yours up after four years. Why?

AM: It wasn’t for me. When you go to law firms, they slot you where they need you. I never got to do the kind of law I wanted to do, which was corporate law.

A friend from Georgetown reached out to me. She’d just started working at the Clinton White House, and there was an interesting job opening. I put my hat in the ring, and I got it. So I moved to D.C. in October of 1999, and stayed there until the end.

CB: What’d you do in Washington?

AM: was the deputy director for the President’s Initiative for One America, the first free-standing White House office in history to focus on closing opportunity gaps that exist for minorities.

We brought thought leaders to the White House to talk about diversity and inclusion, and also created materials to inspire people to have race dialogues in their communities. The idea was that if we sat down and listened to each other, we’d realize we had a lot more in common than what divides us.

CB: How’d you go from working on the president’s cabinet to writing about his kitchen cabinet?

AM: The short answer is unemployment. In 2001 I was in D.C. looking for work. I went to the bookstore one day, where I saw a book about Southern food. I realized the achievement in African-American cookery had yet to be written. I emailed the author out of the blue. Ten years after “Southern Food: At Home, on the Road, in History” came out, John Egerton confirmed that nobody had taken on the task of writing a comprehension history of soul food.

CB: Your book, Soul Food, came out in 2013. Were you writing it for 12 years?

AM: I returned to Denver in 2001 for a job at Bell Policy Center, a progressive think tank that gained prominence for showing the intended and unintended impacts of TABOR. I was ready to write my book in 2006, and then an unexpected thing happened: A democratic governor won Colorado. In 2007, I became the deputy legislative director for Gov. Bill Ritter Jr. By the end of his first term, I was a senior policy analyst working on military and veteran issues, and eventually a point person for the Colorado Campaign to End Childhood Hunger.

Then surprisingly, Gov. Ritter decided not to run for re-election. I went all-in on my book about soul food. Two years later, it came out.

CB: The following year, in 2014, you won a James Beard Award for the book. Did that solidify your decision to become a full-time author?

AM: Not exactly. In 2013 I took my current day job as the executive director of the Colorado Council of Churches. We’re the ones who host the Easter sunrise service at Red Rocks.

CB: So you’re one of those people who doesn’t need sleep?

AM: My day job is 60% time. The food writing is my side hustle. In 2017, my second book came out, about African-American presidential chefs. I was looking through old newspapers and noticed frequent references to African-Americans who’d cooked for presidents. But there were only eight stories written on the topic. I decided to research it, and discovered 150 African-Americans who had cooked for presidents from Washington to the Obamas. I know my book is just scratching the surface.

CB: The President’s Kitchen Cabinet was nominated for a Colorado Book Award and an NAACP Image Award for Outstanding Literary Work Nonfiction. Tell us more about your writing background.

AM: There’s nothing to tell. My only training was in legal writing. I was shocked when I won the James Beard Award.

CB: After setting yourself apart as a soul food scholar, how’d you end up writing your forthcoming book, Black Smoke?

AM: It was inspired by a traumatic experience that happened in 2004. I was watching the Food Network. Paula Deen had a special on barbecue, and after the show, as the credits were rolling, I realized she had not talked to one African-American chef.

That spurred me to do some research. I could have been overestimating the Black influences, so I decided to look into the history of the cuisine. And I was right. It’s almost like you have to go out of your way not to mention African-American contributions to barbecue.