Mining the rich history of Idaho Springs

Investors see a golden opportunity in Argo Mill

Allen Best //September 16, 2016//

Mining the rich history of Idaho Springs

Investors see a golden opportunity in Argo Mill

Allen Best //September 16, 2016//

People chomp at the bit for history and authenticity. Think of the Brown Palace and its storied guest list. Or the brightly painted Victorians of Aspen and Telluride. Or even the Broadway hit musical based on the intrigues of founding father Alexander Hamilton. We love a good story, and even better if it’s true.

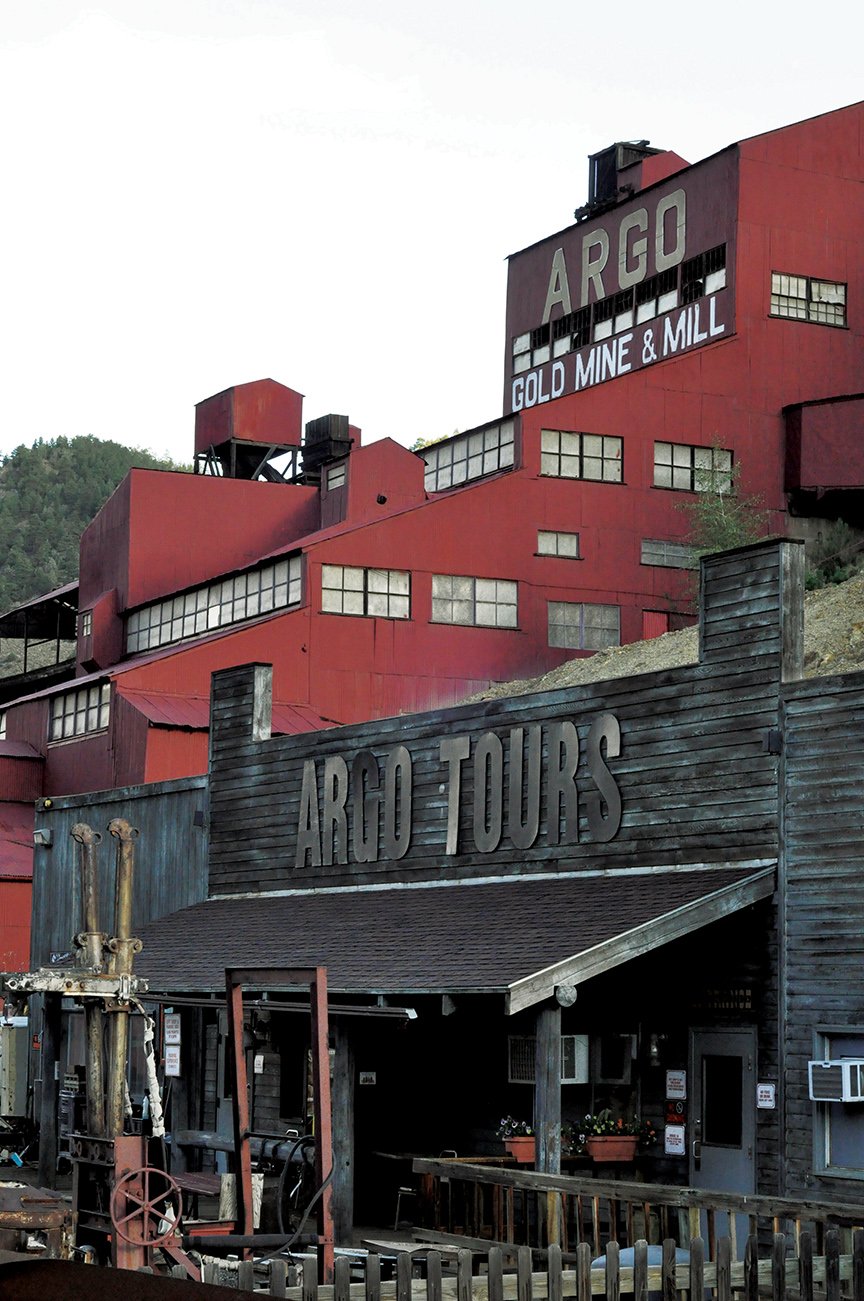

But how about an old industrial site? In Idaho Springs, investors, led by a pair of local residents, have great ambitions for the 27-acre Argo Tunnel and Mill site, where actual milling hasn’t taken place since 1943. Reinvented as a museum in 1977, the Argo does a respectable business, drawing 40,000 visitors a year. The investment team, though, imagines much more: a 160-room hotel, conference center, and other enhancements focused on mining history.

Among the six investors is Dana Crawford, who helped transform Denver’s mindset in the 1960s in her call to preserve the old buildings of Larimer Square. Since, she has been involved in the redevelopment and preservation of the Oxford Hotel, Union Station and, as a developer herself, the Flour Mill Lofts, all of them located in Lower Downtown.

Steeped in history

Idaho Springs has a deep history in Colorado. It was the site of the state’s first major gold discovery in 1859, at the confluence of Clear Creek and Chicago Creek, now identifiable as the central I-70 exit for Idaho Springs. The Argo Tunnel came much later. The main problem it attempted to solve was a common one in hard-rock mines: too much water. Pumps were operating 24 hours a day. The mines were mostly located around Central City, just 20 minutes from Idaho Springs by road, but four miles over a mountain ridge.

That’s about the same distance from the Denver Zoo to Coors Field. Mining speculator Samuel Newhouse had the idea of draining the mines with a long tunnel sloping downhill toward Idaho Springs at a grade of half of one percent. In addition, the tunnel provided a way to extract ore more economically, while also improving ventilation in the methane-plagued mines. With English investors providing the money, the tunnel was bored from 1893 to 1910.

Driving through Idaho Springs on I-70, it’s hard to pick out the tunnel portal on the south-facing hillside across the valley. The Argo Mill is seen more readily. It has red corrugated-iron exterior panels over a steel frame and is terraced into the mountain, standing seven stories high. To the east, yellowed rock litters the slope overlooking Clear Creek. Some of this is rock excavated from the tunnel, but there’s also mine tailings, the refuse after ore had been processed in the mill to extract rare metals.

Residential response

Local pride permeates this effort of economic revitalization. Among the team that purchased the Argo Mill in January was Bob Bowland, a city council member. He grew up in Idaho Springs. His ancestors arrived here in 1873, and family lore suggests they had to dawdle on a train in Clear Creek Canyon to allow President Ulysses Grant’s passage on another train to Central City. Bowland himself spent much of his career elsewhere, working primarily as an air quality control specialist in suburban Denver. He returned to Idaho Springs in the 1980s.

White-haired and slightly hunched, Bowland exhibited the exuberance of a boy with a new Christmas toy while leading guests from the tunnel through the labyrinth of the mill on a hot July day. “Gold was the main thing here,” he said, explaining the noisy, dangerous industrial processes used to pulverize the rock. Once the rock had been reduced to pebbles, chemicals were used extract the gold.

Can the Argo Tunnel and Mill produce new gold for Idaho Springs? The town has been doing pretty well already. The city has as many restaurant seats as people – about 1,700. Even during the recession, city tax revenues held steady. The town continues to invest in its future. Colorado Boulevard, the town’s major east-west thoroughfare, this year is being redone at a cost of $22 million. In the works is a 250-space parking garage for downtown businesses, to be located near Tommyknockers, the brew-pub.

“We lose a lot of business because people drive around downtown and say, ‘I can’t find a place to park, so we are going elsewhere,’” reports city manger Michael Hillman.

Creating a destination

To Mary Jane Loevlie, modest prosperity is not enough. She wants to make Idaho Springs a destination, not a drive-through town. She’s the chief executive of Shotcrete Technologies, a small company with a worldwide market for its produce among mining companies. She’s a key partner in the project and, like Bowman, a native of Idaho Springs.

“We have been ignored for so long,” she says. She blames post-World War II highways. Even before the federal government began financing interstate highway building, Idaho Springs was bypassed in the late 1950s by the future I-70. Completion of Eisenhower Memorial Tunnel in 1973 made it easy to drive from Denver to Summit County.

Conversely, Denver became easier to reach for Idaho Springs residents. Today, you can’t find a lumberyard, a hardware store or even a full-time doctor in Clear Creek County. For that matter, a third of the residents of Idaho Springs drive daily to jobs in metro Denver. It is, in many respects, a suburb. Loevlie, who has been involved in the mining industry, thinks that proximity should work to the advantage of Idaho Springs. Denver, she points out, is just 35 minutes away.

From the yellow mine tailings, investors envision a restaurant, a distillery and an REI-type store with climbing walls and retail goods needed for outdoor adventures. Clear Creek, they point out, is the second busiest waterway in Colorado, behind only the conveyor belt of whitewater boats on the Arkansas River near Buena Vista in summertime.

The Peak to Plains trail will arrive at the foot of the Argo in the next five to 10 years, putting it within biking distance of Golden. They also envision terraced housing built into the mountain. A master plan is being drawn up, with a goal of having something to show town authorities – and investors – by October. In the meantime, the Argo last year drew 40,000 visitors, providing enough revenue to meet the cost of the purchase.

Crawford’s vision

Crawford rejects the suggestion that industrial sites don’t lend themselves to development as destinations. She points to the one-time Pride of the Rockies flourmill, located near Coors Field, she helped convert into lofts.

“I live in a building that was a flour mill at 2000 Little Raven St., and it was among 15 flour mills that used to line the South Platte River. It was turned into a condominium building that has a lot of style and popularity.”

The Argo Mill, she contends, can be leveraged into a 21st century attraction. “It depends upon the quality of the facilities that are built, but in terms of its location, its importance, its visibility, I believe that it has all the makings of a really very superior destination in the collection of Colorado historic stories.”

Crawford’s prominence in historic preservation is reflected in her name on the hotel at Union Station, used by another developer in honor of her contributions in Denver. She’s also been asked to help create an economic revitalization effort to gussy up Trinidad, once a center for coal-mining communities. But she has not been invited, she said, to participate in arguably Colorado’s most massive historic redevelopment project, just now getting underway. That project is the National Western Stockshow complex along I-70, a key part of Colorado’s agriculture heritage. But redevelopment there will likely enhance property in nearby Globeville, which once was a site of the Asarco and other smelters of ores from Colorado mines – including the Argo. The stock show redevelopment will require massive investment, publicly estimated at $1.1 billion.

Developers in Denver acknowledge Crawford’s credibility as an advocate for historic preservation. But whether her involvement in the Idaho Springs project attracts other investors is a different question.

Money and patience

No doubt, redeveloping the Argo site will cost lots of money. It’s part of a Superfund site designation that has led to improved water quality in Clear Creek. Investors think they can build over the old mine tailings. “We’re not doing this on the cheap. It’s not a pipe dream,” Loevelie says.

But if history repeats, it will not be a dream quickly realized. The Argo required patience and never made anybody a fortune. The phrase “gold mine” may connote great wealth, but the Argo’s main value was, in fact, to enable continued operations of mines whose lower-grade ores could not otherwise justify the increased costs of transportation from Central City.

Even so, the mill operated only sporadically after 1910 before closing for good in 1943. Newhouse, the mining speculator behind the tunnel, became fabulously wealthy in his day, but from copper deposits in Utah’s Bingham Canyon, not from the Argo. He got rich, just not quickly.