Shallow Risk vs. Deep Risk

In response to the apocalypse du jour, investors often react by making portfolio adjustments to avoid potential regret

Timothy J. Keating //October 29, 2018//

Shallow Risk vs. Deep Risk

In response to the apocalypse du jour, investors often react by making portfolio adjustments to avoid potential regret

Timothy J. Keating //October 29, 2018//

A few years ago, numerous news outlets picked up an apocryphal story about a study purportedly completed by Fidelity Investments, concluding the most successful investors were either dead or completely inactive – because they had forgotten they had accounts. Although Fidelity never published such a study, the alleged conclusion was accurate: Your retirement portfolio will be best served if you take no action in response to current events of any kind.

There are many rigorous studies that thoroughly document:

- The results of attempting to time market entries and exits – a fool’s errand.

- The cost of missing the top x best performing days in the market over a given time period – massive.

- The effect of investing at the worst times, market tops, over a given cycle – utterly negligible.

- The “behavior gap,” a comparison of the dollar-weighted returns an average investor in a mutual fund experienced by moving in an out of the fund to the time-weighted returns of the mutual fund itself – anywhere from 25 percent to 50 percent lower over five- to 30-year horizons.

Average investors who engage in any of these behaviors may face the ruinous result of outliving their money. Contrast this financial failure with the alternative – money that outlives the investor. Sadly, for those without the benefit of a financial adviser who stresses behavior as one of the key governing variables in determining real-life investor outcomes, financial failure is a very real possibility.

DIFFERENT TYPES OF FINANCIAL RISK

In his book “Deep Risk,” Bill Bernstein highlights the financial differences between shallow and deep risk:

Risk, then, comes in two flavors: “shallow risk,” a loss of real capital that recovers relatively quickly, say within several years; and “deep risk,” a permanent loss of real capital. Put into different words, shallow risk, if handled properly, deprives you only of sleep for a while; deep risk deprives you of sustenance.

STOCK RISKS ARE SHALLOW; BOND RISKS ARE DEEP

Stock market corrections and bear markets clearly fall into the shallow risk category. The drops are often sudden and severe – and always terrifying. Equities are far more volatile than bonds, and the bumpy ride is the reason for the higher returns. But equity volatility is not the same as risk. Volatility is a short-term disturbance, whereas the long-term returns from equities are enduring. Equities are a good investment because they go down temporarily and up permanently.

In stark contrast, the risk of owning bonds as a long-term investment can be very high, although many investors find this counterintuitive. The cause for concern is inflation.

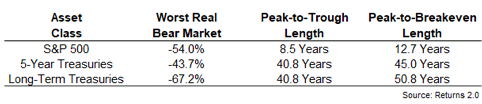

In a recent post, “The Worst Kind of Bear Market,” blogger Ben Carlson compared the worst “real,” or inflation-adjusted, bear markets in stocks to those of bonds.

From November 1940 through September 1981, the real losses of five-year and long-term Treasurys were nearly 44 percent and just more than 67 percent, respectively. Although the nominal rates of return for the Treasurys were about 4.7 percent annually over the 45- to 50-year bond bear market periods, inflation ate up all of the annual coupon and then some.

And if these long-ago periods seem irrelevant, consider the present. Even with the recent runup in the 10-year Treasury yield to just more than 3 percent, inflation is 2 percent, providing a measly real return of 1 percent – and that’s charitably assuming no future uptick in the inflation rate.

ASSET ALLOCATION IMPLICATIONS

The difference between the shallow risk of equities and the deep risk of bonds guides our asset allocation philosophy.

In addition to having a cash reserve fund sufficient to cover one or two years’ worth of living expenses (depending on your employment status), we advocate investing funds to cover foreseeable capital needs over the next five years in Treasurys or investment grade bonds (or an equivalent bond fund) with a corresponding maturity. Investing the remainder of the portfolio in equities will enable you to grow your capital and cover the always-increasing costs of a typical three-decade retirement.

Or, to quote Bernstein:

“Capital managed for near-term liabilities should be guided by shallow risk, while capital managed for very long-term liabilities should be guided by deep risk.”

THE ACID RAIN OF NEGATIVE MEDIA

This discussion would not be complete without a look at the underlying behavioral motivation that gives rise to the obsessive focus on shallow risk.

Earlier this year, our friend Nick Murray published an article titled “The Acid Rain of Negative Media,” in which he made three key points:

- The narrative of financial journalism is relentlessly and remorselessly biased to the negative.

- Over time, the cumulative impact of this negativity inevitably cracks even the most dedicated investors’ best intentions to remain patient, disciplined and focused on the long-term.

- In response to the apocalypse du jour, investors feel they need to react by making portfolio adjustments to avoid the potential regret of incurring losses and/or just feeling stupid.

This inevitably leads to bad investment decisions based on short-term – and always negative – stimuli.

Ulysses put wax in his men’s ears and had them tie him to the mast to avoid the deadly consequences of hearing the Sirens’ songs. Likewise, you must block out the media noise and avoid the adverse investment consequences of reacting to shallow risk. Think in decades, not days.

BEHAVIORAL TAKEAWAY

The availability bias is the human tendency to think examples of things that come readily to mind are more representative than is actually the case. On the positive side, the availability heuristic enables us to make quick decisions and judgments – which, in many of life’s circumstances, can range from beneficial to essential. On the negative side, reacting to recent events can lead to deeply flawed decisions for investment horizons that typically span decades.