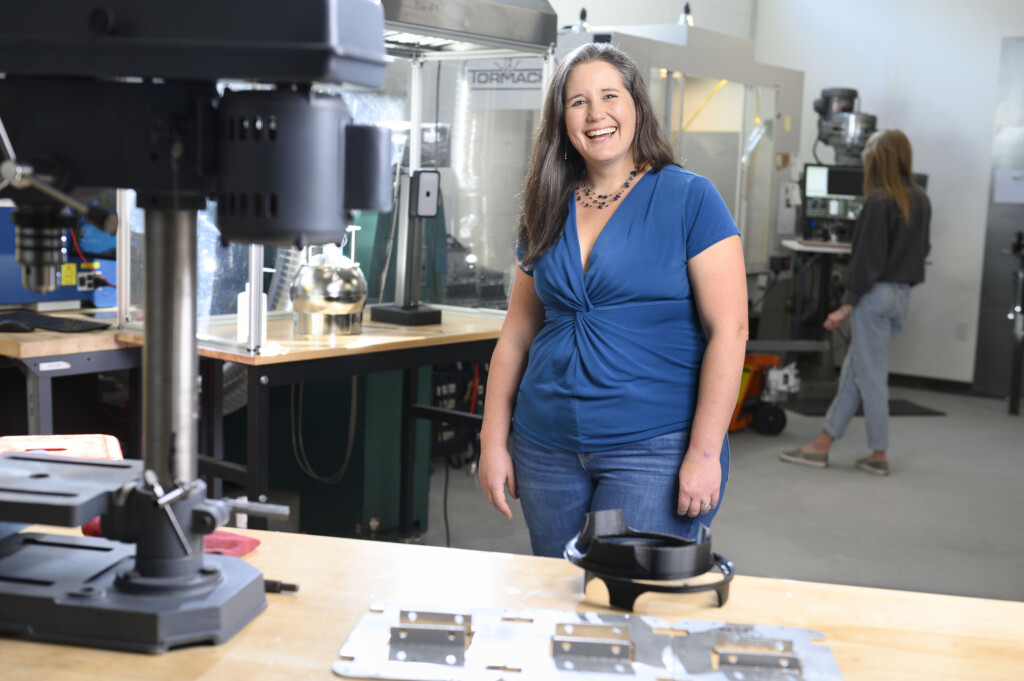

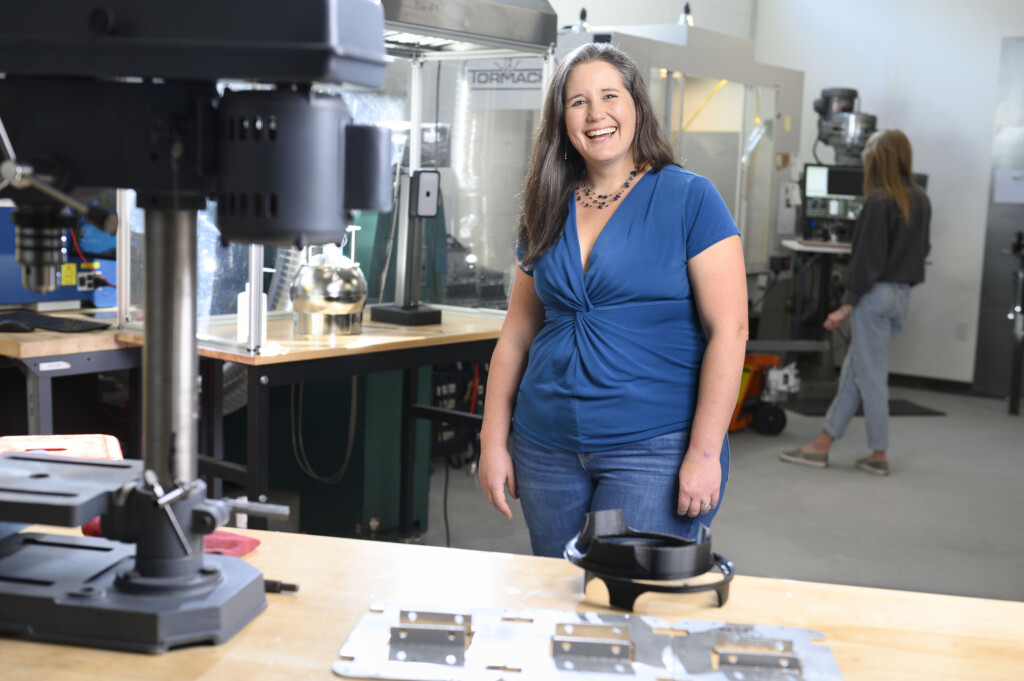

Natasha bond joined ERI group as president in 2021. The company has been helping clients bring medical devices to market since 1988.

“we offer development, manufacturing quality, and regulatory. Some projects touch all of those and some projects touch one of them,” says bond. “our job — my job — is to fill the gaps in the client’s capabilities to enable them to hit the milestones they care about. There’s no minimum or maximum, there’s no one size fits all.”

After working in medical devices in Texas, bond moved to Colorado for a job with Vention Medical (Now Nordson Corp.) In 2014. “I just absolutely loved it out here, so it was definitely by design that we moved,” she says.

The 75-employee ERI group rebranded from evergreen research in early 2022 before merging with Denver-based link product development in july.

Natasha Bond, 44

Golden, CO

Hometown: Manchester, England

What she’s reading: “I have about eight books going at any one time,” she laughs, highlighting three currently on her nightstand: “Managing the Professional Service Firm,” by David Maister; “The Wind in the Willows,” by Kenneth Grahame; and “Round Ireland with a Fridge,” by Tony Hawks

ColoradoBiz: How did you get into the medical device industry?

Natasha Bond: Way back when, I intended my career to be focused on automotive. I actually, pre-college, was very much into motorsports and spent a couple of years doing that. I decided I wanted a little bit more intellectual life, got myself to college, got my engineering degree, and fully expected to spend my career in autosport or automotive.

Through a little bit of taking the door that opened and a little bit of luck, I actually ended up working for PA Consulting Group, who had an automotive division. They also had a consumer products division and a healthcare and medical device group. I took the opportunity to experience all of that different stuff at the beginning of my career and found so much motivation and personal pride in doing something that was going to help people that needed it, as opposed to doing something that, you know, helped people go 5 percent faster or do it on 5 percent less fuel.

CB: What brought you to ERI Group?

NB: For the three years prior to joining, I was actually leading a bit of a double life. I was COO of a startup four days a week and then running my own consultancy two days a week. Honestly, both of those jobs each needed about six days a week, as did my family, and there wasn’t enough of me to go around.

I know the previous owners quite well, and I actually phoned them up looking for safe landings for my clients. I have a lot of emotional attachments to the technologies I work with and I certainly don’t want my choices to impact other people’s business. They mentioned they were looking for a new lead for what was then Evergreen Research, and it just felt like an amazing door to see if I could step through.

I was incredibly lucky that I managed to take a set of clients and a consultancy that I thought I was going to have to shut down, fold it into 35 years of experience and an amazing team and a huge opportunity, and then turn my day job with my startup into a client. That is the kind of business acrobatics that I don’t ever expect to be able to repeat.

CB: Evergreen Research recently merged with LINK Product Development to form ERI Group. What was the rationale for that deal?

NB: First and foremost, my desire with ERI is to make sure that, between what we have in-house and the community and contacts that we have, we can support medical innovation whatever way [clients need]. In terms of industrial design, human factors, engineering, usability, that wasn’t something we had in-house when I joined what was then Evergreen, but it’s something I’m very passionate about. I’m a big believer that if you don’t make things easy to use and appealing to adopt, then they won’t be adopted and used, so I really think that particularly usability engineering is just really critical.

I have a huge amount of respect for [LINK founder] Marc Hanchak and his team, and we were already working together. The point at which the merger happened, I think that ERI was about a third of their portfolio anyway. So honestly, it was just a very natural progression of what was already a very strong working relationship — and I think that’s borne fruit in what’s happened in the last few months.

CB: How has the medical device industry changed in your decade-plus of experience? And what was the impact of the pandemic?

NB: You can get an app to market a year, you can get most consumer products to market in a couple years — we’re looking much more at four to six. Obviously, the pandemic changed the way that we worked a bit. It created a bunch of chaos at the FDA as they were dealing with an influx of people trying to help with the pandemic, and it created a somewhat temporary change of focus away from some of the more traditional things that people cared about, like oncology and heart disease, into COVID tests and antiviral measures. I do think it’s going to take the FDA a couple years to work their way out of a mess of their own creation, but we are working gently with them as they try and figure that out.

In terms of bigger macro changes over the last decade or so, we’re seeing a lot more innovation going to at-home use versus surgical. If you asked me in the mid-’90s what I was seeing, I would say, “We’re seeing more open surgery going to minimally invasive surgery.” The 2000s was really about the expansion of the scope of those minimally invasive surgeries into things that are much more complicated and much more use of multifactorial data to produce more intelligent diagnoses. Now I think it’s about pushing that care earlier into the cycle, pushing it into the home, pushing it into more accessible health-care situations — the rural health centers or the primary care — from the hospital, and obviously a lot more data and a lot more connectivity and a lot more visibility for people within that whole ecosystem.

ERI works with about 30 percent large, strategic, multinational, public companies and 70 percent startups. On the startup side for the last decade, there’s been a lot of focus on: “What is the value proposition? What are the health economics?” They really have to get a solid case for benefits going before they’re going to get funding. From that perspective, I think life’s gotten harder than it was in the ‘90s or maybe 2000s when it was: “If you’ve got solid science, the money will work itself out and somebody will figure out how you’re going to get paid for it later.” I don’t think that works anymore.

CB: Are there any recent highlights of products and projects that ERI Group has worked on?

NB: In our industry, achieving a quality certification is a pretty big deal. A couple of weeks ago, we actually got two clients through the major international quality certificate in the same week without a single finding. Just to put that in context, if you have a major finding, typically you’ve got to remediate before you can get your certificate. You can have up to 15 minor findings and still get a certificate. Typically, prior to being at ERI, if I got less than six, I felt like I’d overprepared. It’s like coming through a driving test with an absolutely clean sheet of paper, and we had two clients come through with a clean sheet of paper in the same week, which I think really speaks to the quality of the work and the quality of the approach.

There’s another one I’m particularly proud of where one of our major clients got their FDA approval for their clinical trials earlier than expected, which — as I’m sure you can imagine — doesn’t often happen. I mean, the government actually getting something across the finish line quicker than normal?

They phoned us up and said, “You know the parts that are due in four weeks? Any chance we can have them in 48 hours?” Supply chains are very difficult right now. These were high-precision, hardened, very complex mechanical systems that we also have to keep completely in control in terms of documentation and traceability, because they’re being used in people.

The team really pulled together. It took every discipline in the company to make it work, but we ended up hand-delivering the product to the client in good time to hit that 48-hour deadline. I’d really seen the team take the attitude of: “Well, yes, of course, we’re going to try to make this happen for you.”

The other one I’m really proud of, given the state of supply chains right now, is the fact that we’re running on a 99 percent on-time, on-quality delivery across all of our product lines. The ability to hold that as a manufacturing metric is a little bit crazy, actually.

CB: What’s your forecast for growth and the future of ERI Group?

NB: We’re aiming for solidly double-digit growth sustainably over the next five years. It’s not about taking business in our sweet spot — although, that’s always been really critical to make sure we have the skill set to deliver — but it’s about making sure that we are seated at the table with the client, right beside them, as the partner.

I had one client phone me up the other day, a major strategic company, and they basically said, “We have an issue. We’d love a second set of eyes on this issue to make sure we thought about it the right way and haven’t missed something, and you guys are the first people we phoned.” And that is exactly my goal for every single team at ERI for every single client. We should be the people they phone any time they have a question, a thought, a concern, or a piece of good news. We want to partner in a way that makes us an integral part of the team.

The other thing I would mention in terms of where we are going for the next couple of years is really an internal focus on culture and rewarding the team for the excellent work that they’re doing, really empowering and enabling the people within the company and making it, honestly, just a really fun, really mutually supportive place to work. That’s something we’ve worked incredibly hard on in the last year.

I want to hire amazingly talented people and give them incredibly important, incredibly complicated work to do. If I can’t empower them to make good decisions and encourage them to support and lean on each other and ask for the help of the hive mind internally when they need it, we’re not going to do as good a job and it’s not going to be as nearly as fun.

Denver-based writer Eric Peterson is the author of Frommer’s Colorado, Frommer’s Montana & Wyoming, Frommer’s Yellowstone & Grand Teton National Parks and the Ramble series of guidebooks, featuring first-person travelogues covering everything from atomic landmarks in New Mexico to celebrity gone wrong in Hollywood. Peterson has also recently written about backpacking in Yosemite, cross-country skiing in Yellowstone and downhill skiing in Colorado for such publications as Denver’s Westword and The New York Daily News. He can be reached at [email protected].

Denver-based writer Eric Peterson is the author of Frommer’s Colorado, Frommer’s Montana & Wyoming, Frommer’s Yellowstone & Grand Teton National Parks and the Ramble series of guidebooks, featuring first-person travelogues covering everything from atomic landmarks in New Mexico to celebrity gone wrong in Hollywood. Peterson has also recently written about backpacking in Yosemite, cross-country skiing in Yellowstone and downhill skiing in Colorado for such publications as Denver’s Westword and The New York Daily News. He can be reached at [email protected].