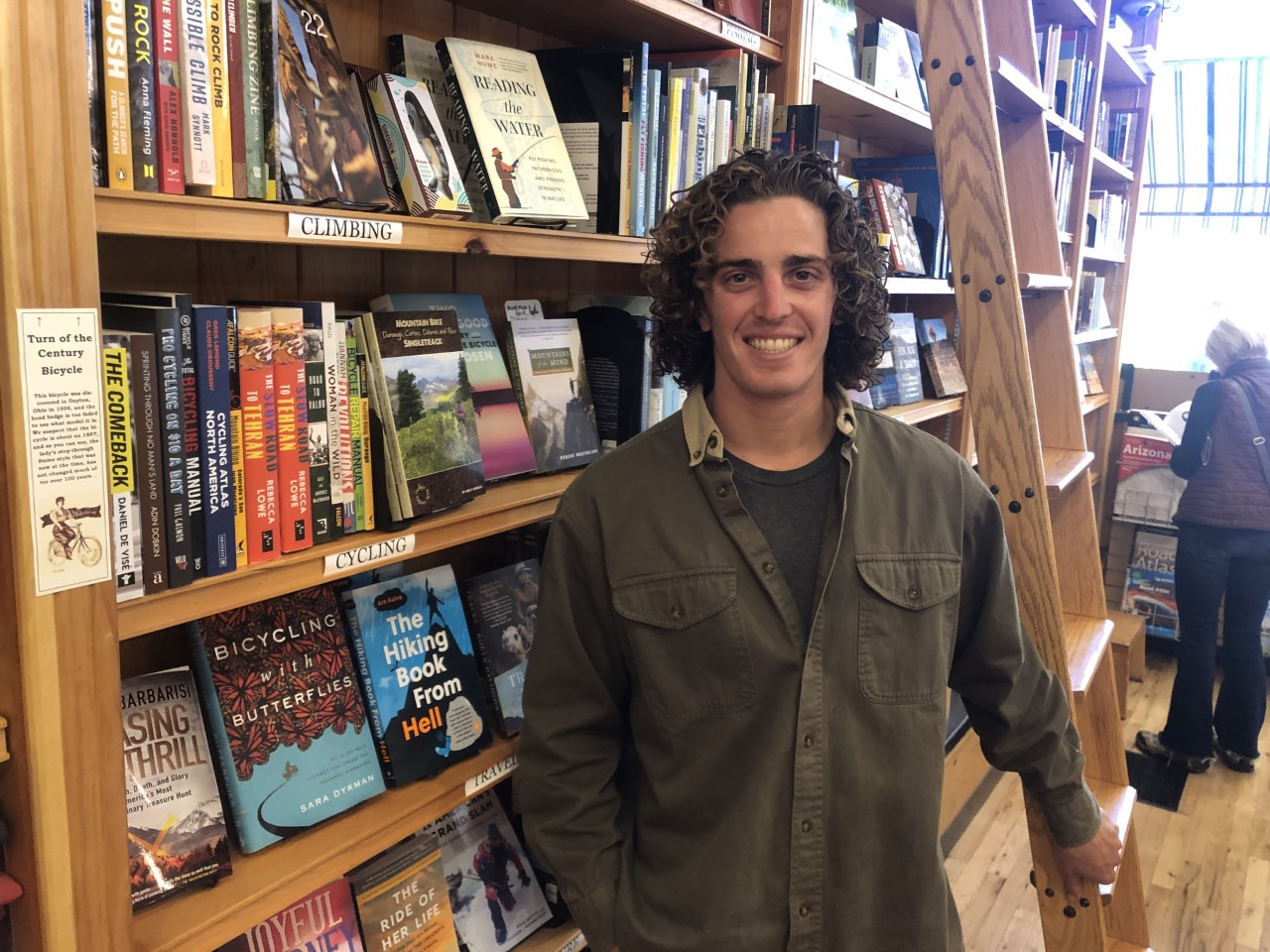

Using wheelbarrows to transport the merchandise, Maria’s Bookshop moved into its current location in an old building in downtown Durango in 1992. Last year, it sold 100,000 volumes, many of them hardbacks.

Tourists constitute about half the customers of Maria’s, a higher percentage during summer when the Durango & Silverton Narrow Gauge locomotives whistle past just a block away. But Evan Schertz, the owner/manager, says it’s local residents who define the bookstore.

“It’s the intentional local support that makes this work,” he said.

When people walk into Maria’s, they see books of nature writing, local travel and adventure, local history and native Americana. Schertz calls these the five pillars of community interest.

“It takes intention for a community to support a bookstore,” he explained. “There are so many easier ways for people to get books now, so the community has to believe in the value of having a bookstore.”

Durango supports booksellers like few other places. It has a second store that sells new books, three more that sell used books, and one, Magpies, devoted almost entirely to magazines. None are part of chains.

READ — Colorado Business Owner Shares the Importance of Shopping Locally This Holiday Season

I was in the Four Corners area in October to investigate the business and cultures of Durango and Cortez. But I also visited Farmington, which is in New Mexico but intertwines with the two Colorado towns.

All three places have roots in resource extraction. Durango was once a supply center for hard-rock mining in the San Juan mountains. It had a sawmill that in 1960 had 100 employees.

And it had a smelter that was reopened after World War II to process uranium to help arm the United States during the Cold War.

Then came the economic shift. The uranium smelter closed in 1962, and the site was cleansed of its heightened radioactivity in the early 1980s, about the time the last sawmill operations occurred. Meanwhile, the Purgatory ski area north of Durango had opened in 1965. Within a 20-year period, Durango’s economy had shifted to amenities and a new culture that extols the landscape rather than extracts. Durango had become something like Boulder but at the intersection of mountains and desert. And like Boulder, it has gained elevated housing prices.

Farmington is almost entirely the opposite, booming with fossil fuel extraction and combustion. Today, it struggles to retain that wealth while it seeks to build its still-smallish tourism-based sector. Cortez ranks somewhere in the middle but with more agriculture than the other two.

Think of Durango as a Subaru Outback, Cortez as a Ford F-150, and Farmington as a Ford-250 XLT.

Common to all three communities is the presence of Native Americans, not surprising given the proximity of designated tribal lands of the Southern Ute and Ute Mountain Ute bands in Colorado and, in adjoining states, the Navajo Nation. All have free tuition at Fort Lewis College, whose campus lies on a mesa overlooking Durango.

Down in the Animas River Valley lies Durango’s lovely old downtown, including the ornate Strater Hotel, a testament to Victorian opulence, and the General Palmer Hotel, the latter named after the Colorado Springs-based railroad builder of the 19th century. The district has all kinds of restaurants, bars and interesting shops and, at the end of the six-block district, a very old-fashioned enterprise, a newspaper, the Durango Herald, family-owned and operated since 1952. With due respect to the historic-district downtowns of Boulder, Fort Collins and Aspen, I’d nominate Durango as the most interesting.

A block off Main Avenue I met with Mark Pearson, who grew up in Aurora, got a degree in natural resource management from Colorado State University, then moved to Durango in 1992. It’s like Colorado’s ski towns, except it has a somewhat warmer, easier climate. Also like ski towns, it had lots of jobs but few fat paychecks. “You just didn’t get hired on at a $75,000 salary. You had to take an odd job and figure out how to make things work.” In that regard, nothing has changed in the last 30 years.

The San Juan Citizens Alliance that Pearson founded carefully watches the oil and gas development in the San Juan Basin, a geological structure 40 miles wide and, beginning at the edge of Durango, 100 miles long. The field has produced 40,000 wells, most of them in New Mexico, and a cloud of methane. They have also produced a bounty of tax base revenue for local jurisdictions. That wealth has been receding. From 2005 to 2022, oil and gas as a share of property taxes for La Plata County, in which Durango is located, dropped from 59% to 16%.

Pearson also pays close attention to the impacts of recreation. He talks about “such a narrow-minded focus on fun” that people lose sight of their own impacts. “It just goes over people’s heads,” he says, “They think, ‘My recreation can’t impact wildlife, can it, because we don’t extract anything.’”

The four corners communities are isolated from major population centers. From Durango it’s 330 miles of mostly two-lane highway to Denver. Albuquerque is 215 miles. Into the 1990s, if you wanted to catch a commuter flight, you mostly went to Farmington. But the Farmington City Council said no to the expense of a longer runway needed to accommodate larger aircraft. It lost commercial service altogether in 2017.

Farmington’s loss has been a gain for La Plata County (Durango-La Plata County Airport). Between 2000 and 2021, passenger boardings grew from 91,000 to 200,000. The airport has six daily flights to Denver, three to Dallas, and two to Phoenix, and local leaders hope to add Delta flights to and from Salt Lake City. Two-thirds of passengers come from the Durango area, with the others from Pagosa Springs, Cortez and Farmington areas.

In Farmington, when I met the mayor, Nate Duckett, at a coffee shop ironically called Durango Joes, he grimaced when I mentioned the airport. The decision was made before his time, but he can see the opportunity that was lost. As mayor, his primary job is to try to leverage Farmington’s assets to hang on to what it was. He has his work cut out. You won’t hear a bad word about fossil fuels coming out of the mayor’s mouth, but he does talk gladly about needed diversification.

Farmington began as an agricultural enterprise, especially of apples. Fossil fuels, though, now define the city. The first development occurred in the 1920s but the big, big booms — interspersed by busts — came after World War II when pipelines were built to export natural gas.

The area also has ample coal deposits. Nine coal-fired units completed in the 1960s and 1970s operated at one time with a total generating capacity of almost 2,900 megawatts. Just two units continue to operate, and they are scheduled to close by 2031.

Duckett has little faith in renewables replacing either the lost power generation or the economic loss to Farmington’s business sector. “You can’t just cut oil, gas and coal out of your economy and then expect to be able to grow, because those private investments are what create jobs, wealth and opportunity,” he said.

An insurance company owner, Duckett was reared partly in the Denver suburb of Northglenn. In the 1970s, his father got engaged in the solar movement, which at that time consisted primarily of solar thermal, not the solar photovoltaics of recent success. Still, it seems to have soured his attitude about the ability of solar and other renewables to replace fossil generation. They don’t, he insists, provide the necessary redundancy.

Farmington has had ups and downs, booms and busts. The city’s museum is not shy about acknowledging this. It’s common in fossil fuel economies. Now, the trendline is toward a long-term bust. This began in about 2008-2009. ConocoPhillips and other big outfits pulled out to pursue better opportunities in emerging oil and gas plays elsewhere in the country. This “giant underground sea of natural gas” that Duckett describes isn’t enough.

“A lot of the older leadership here was concerned that we didn’t have a future,” says Duckett. “We had to address our internal belief systems.”

READ — A Zero is Not OK: Some Colorado Representatives are Failing Us on Energy

City economic leaders began plotting how to create a broader, more diverse economy. Some hope for railroad access, allowing export of manufactured products. Other work has focused on expanding tourism. Focus groups with small-business owners were convened, consultants hired and, in 2018, a director of outdoor recreation was hired, all in the interest of creating a brand built around Farmington’s family orientation and the outdoors. The city does have three rivers, including eight miles of trail along the Animas. It even has a flyfishing guide.

With these and other merging amenities, Farmington hopes to appeal to both retirees and those in location-neutral jobs or businesses from Colorado’s Front Range or chilly Midwestern towns and cities. Greatest of its virtues may be its housing prices. Farmington’s median-area home prices of $300,000 compare to Durango’s $625,000.

Housing prices partly explain the commuting among the three cities. Durango has the most service jobs, and hence the daily inhalation of workers from Farmington and other outlying but lower-cost towns. In some cases, the reverse happens. Farmington, for example, reportedly pays nurses better.

Farmington gets busy on weekends, but not necessarily your traditional tourists. It’s a shopping hub with all the big boxes: Target, BestBuy, Lowe’s, plus the chain restaurants. You drive to these places because – well, that’s what you always do in Farmington.

Appropriately, I drove to Amy’s, the city’s lone bookstore independent of a church since Hastings, a chain store, pulled out. Amy’s deals almost entirely in used books, paperbacks mostly. The paperbacks, explained Amy, offer readers escape and entertainment. I did find three used volumes of Western Americana that demanded my money. With those books and a lecture about the superiority of Republicans, I set out for Cortez, an hour away.

Cortez has been among my favorite Colorado towns since I first visited as an adolescent on a family trip to Mesa Verde National Park. I was smitten by a motel housekeeper. She was an older woman, probably a junior in high school. The town, at the edge of the desert Southwest, seemed exotic compared to the farm town in the opposite corner of Colorado where I grew up.

Joe Keck has lived in Cortez since he was in first grade. He later served several terms as mayor, operated two small businesses— a Hallmark cards store and a J.C. Penney’s outlet— and has worked in business development for five decades. His relationships have included both the Southern Utes and the Ute Mountain Ute bands as well as Fort Lewis College.

The town has had a long history in agriculture, mostly dryland. Since the Dolores River was dammed in the 1980s to produce McPhee Reservoir, irrigation has expanded. The Ute Mountain Utes were able to put 7,500 acres under cultivation. Another big chunk of the economy has been extraction of carbon dioxide from the largest underground deposit in the world. It is piped to West Texas where it is used to extract oil from the Permian Basin wells.

Tourism comes and goes, but the outdoors always beckons. In addition to Mesa Verde, there are several national monuments, including most recently Canyons of the Ancients. Osprey, the manufacturer of backpacks and other outdoors goods, relocated from California to Cortez in 1990 and still has about 100 employees although the manufacturing was recently transferred to Ogden, Utah, for closer access to rail and airport. As of a few years ago, half the sales were international.

Cortez is not Durango. It’s a blue-collar town, and college diplomas are not standard. In most things, it lags Durango by about 20 years. But it’s not static, either. And it perhaps has a more balanced economy than its neighbors.

In something of an echo of what I heard in Farmington, Keck told me of greater integration of the indigenous populations into the economically dominant Anglo population of Cortez. Native Americans, for example, have been getting advanced training in nursing. It wasn’t always that way.

“There are a lot more Navajo people especially and some Utes, too, who are working and living here. Navajo people have integrated into the community. That’s a real positive,” he said. “Most of my growing-up years, it was just such a separation between the cultures and the communities.’’

The next morning, we visited a farmers market, notably different than most I have visited in that the vendors were obviously local. Around Cortez, self-sufficiency is prized. Many people live off the grid and supply their own food. One store clerk confided the difficulty that can pose. She had grown fond of certain of their hogs and had made it clear to her husband that they were to be spared the knife. Others among the hogs, she said, she didn’t much care.

Like Farmington, the bookstore in Cortez traffics mostly used volumes, particularly paperbacks. I did find three steals of non-fiction volumes about Western history. Paying for them, I also noticed a passel of new books, mostly those alleging political conspiracies. To the side was a conspiracy theory book of greater age: Hitler’s “Mein Kampf.”

A couple hours later, I was back in Durango again, sitting on Main Avenue in front of Carver Brewing Co. The business had started as a bakery in Winter Park in 1983 when I lived there, then the brothers — Jim and Bill — had relocated to Durango with its warmer climate and more robust economy. The brothers are said to have a friendly rivalry with U.S. Sen. John Hickenlooper, who opened Denver’s first brewpub. Wisconsin natives, they started brewing beer in 1985. The brewery proclaims itself the first brewpub in the Southwest. Now, similar to Maria’s Bookstore, it is being operated by a second generation.

On the menu at Carvers was a craft beer, Iron Horse, a nod to the local Iron Horse Bicycle Classic, a race started in 1971. Durango’s food and beverage businesses brim with local nods. The previous evening in Cortez I had enjoyed a brew, Blue Corn John, a traditional dark Mexican beer but made from blue corn grown by the Ute Mountain Ute Bow & Arrow Farm. In Farmington, Three Rivers Brewery had a Daily Forecast Hazy Pale ale. Whether that spoke to the sky during a time of coal combustion, I couldn’t be sure.

At Carvers I met a former Durango mayor, Dean Brookie, an architect who grew up in Littleton and went to college in Boulder. There, while working for Denver’s OZ Architecture, he worked on restoration of Chautauqua as well as design of the Pearl Street Mall. He moved to Durango in 1980 and promptly became involved in designation of the city’s Main Street of Victorian buildings a national historic district.

In 1980, he says, there was constant paranoia whether the train would run. An entrepreneur purchased everything for $1 million, downtown real estate and steam locomotives included. Now, with the recreation economy firmly in place, Durango gets accused of being elitist. Like others, he finds the perception misses the mark. Trending liberal? Yes. That’s Durango. But he also points to the high incomes and the big, big houses of fossil fuel executives in Farmington before the decline of fossil fuels as another way to understand elitism.

Still, pointing across to an ice cream parlor, Brookie ventures that owners pay $6,000 a month for the Main Avenue space. “That’s a lot of ice cream to sell,” he said. The same space in Farmington might cost $1,500, he added, “but nobody is walking around.”

As for Cortez, Brookie observed that the town has potential for more of a tourism and recreation economy as a starting point for exploration of the Southwestern canyon country.

The next morning, we set out for the Front Range again. It may have been a first, but I had visited Durango without buying a

single book.

Allen Best has been writing about Colorado water steadily for the last 20 years for ColoradoBiz, Headwaters magazine and now for his own publication, Big Pivots.

Allen Best has been writing about Colorado water steadily for the last 20 years for ColoradoBiz, Headwaters magazine and now for his own publication, Big Pivots.