Monday morning provided some corporate M&A fireworks as Chevron announced the purchase of Colorado-based PDC Energy. It will acquire all of the outstanding shares of PDC in an all-stock transaction valued at $6.3 billion, or $72 per share.

The deal makes Chevron an even more formidable operator in Colorado by tacking an additional 275,000 net acres in the the Denver-Julesburg (DJ) Basin onto its existing position after acquiring Noble Energy three years ago.

PDC also holds 25,000 net acres in the Permian basin, a prolific oil bas in Texas responsible for America’s surge in oil production. It’s split of assets between the DJ and Permian basins makes Chevron a sensible strategic buyer as it can leverage operational synergies in both area with the company expected to capture about $100 million in annual operational synergies.

“PDC’s attractive and complementary assets strengthen Chevron’s position in key U.S. production basins,” said Chevron Chairman and CEO Mike Wirth. “This transaction is accretive to all important financial measures and enhances Chevron’s objective to safely deliver higher returns and lower carbon. We look forward to welcoming PDC’s team and shareholders to Chevron and continuing both companies’ focus on safe and reliable operations.”

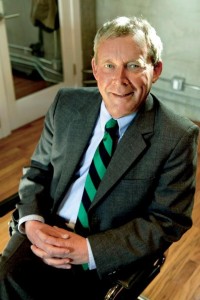

“The combination with Chevron is a great opportunity for PDC to maximize value for our shareholders. It provides a global portfolio of best-in-class assets,” said Bart Brookman, PDC President and CEO. “I look forward to blending our highly complementary organizations, and I’m excited that PDC’s assets will help propel Chevron toward our shared goal for a lower carbon energy future.”

Transaction Benefits

In a news release, Chevron highlighted four key developments about the deal, noting it is:

- Complementary to Chevron’s operations in important U.S. production basins

- Adding 10% to oil equivalent proved reserves for under $7 per barrel

- Accretive to earnings per share and return on capital employed (ROCE)

- Expected to add $1 billion to annual free cash flow

Shortly after the news broke, Andrew Dittmar of Enverus Intelligence Research, a nationally-recognized oil and gas M&A analyst, offered his in-depth review of the deal.

“The acquisition of PDC provides Chevron with high-quality assets expected to deliver higher returns in lower carbon intensity basins in the United States. PDC brings strong free cash flow, low breakeven production and development opportunities adjacent to Chevron’s position in the DJ Basin, as well as additional acreage to Chevron’s leading position in the Permian Basin.”

Besides favorable ESG metrics and the immediate financial accretion that comes from buying from the smaller-sized E&P peer group that has been discounted by the market, Dittmar pointed out that focusing on the DJ Basin likely allows Chevron to acquire undeveloped upside at more favorable pricing. The company looks to have paid less than $5,000 per acre with more than 80% of the total deal value allocated to existing production. That compares to the Permian Basin where equity valuations for companies with equivalent inventory tend to be higher and M&A markets more competitive. Land containing equivalent quality inventory has priced at north of $20,000 per acre in recent M&A in both the Midland and Delaware basins.

The Colorado assets do come with some increased regulatory risk, but the worst case for stopping permitting feared several years back has largely not come to pass. Companies have successfully been able to secure years of drilling permits and the PDC assets’ location in Weld County helps alleviate future development concerns versus more populated portions of the play.

With its large exposure in the play and position in the market, Chevron is well positioned to be a champion for oil and gas production in Colorado.