From Aaron Million’s 12th-floor office in downtown Fort Collins, you can see Wyoming in the distance. Depending upon the route, it can be 3,000 feet uphill. The downhill side of that equation, however, has become a key feature in Million’s pipeline vision.

Million wants to import water 338 miles from the Green River in Utah just below Flaming Gorge Dam. The water would flow through pipelines paralleling Interstate 80 across Wyoming before tumbling into Colorado’s northern Front Range. In that tumble, Million and his company, Water Horse Resources, say they intend to build pumped-storage hydro projects to generate electricity when most needed.

The company’s diversion plans call for delivering up to 55,000 acre-feet of water annually to the Fort Collins and Greeley area. This would be roughly comparable in size to water from the Winter Park area imported to Denver and its suburbs through the Moffat Tunnel.

That new pumped-storage element will produce income along the way, but the water itself will have many other uses. “Almost all of the water supplies in Colorado are seasonal,” Million says.

“We will be able to deliver water throughout the year. But it is also a project that will have environmental benefits by augmenting existing stream flows, helping renewable green energy, helping the agriculture side, and alleviating some of the municipal demand. Most of the projects in Colorado were developed with singular purposes. We are not.”

Million’s project may be the most audacious ambition yet in Colorado’s century-long quest to dismantle the geography of native water flows. In Colorado, more than 70% of the water originates west of the Continental Divide, but close to 90% of the state’s population lives to the east, mostly along the Front Range. The Moffat Tunnel, which began diversions in 1936, was the first major transmountain diversion. Now, the mountains have become a Swiss cheese of diversion tunnels. Anywhere from 30% to 50% of water along the Front Range originates on the Western Slope in any given year. As well, Western Slope water augments native flows to irrigate farms along the South Platte and Arkansas rivers and their tributaries.

READ — America’s Energy Future Depends on Cultivating the Next Generation of Talent

This, however, would be different from all others. It would be a private enterprise, while all the other major projects have had public sponsors. It would also divert water from another state. That adds a complication.

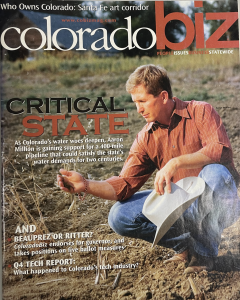

Million, now 62, first conceived of this new plumbing in 2002. It was a summer of searing drought. Denver spray-painted the parched grass green at City Park before an unveiling of a statue. He was then a graduate student at Colorado State University. Four years later, I met him one afternoon at a restaurant on College Avenue in Fort Collins. ColoradoBiz delivered the first story.

Those two decades could not have been easy for Million. Colorado’s wizened water leaders pushed back. High cost and high risk, they said. He’s had trouble securing permits. But after spending four or five intermittent years on the project during the last two decades, he’s back at it full-time.

Nine months ago, Million announced a new relationship with Florida-based MasTec, an engineering and construction company that is ranked 429 on the Fortune 500. Even before then, Million had recalculated the project to harness the power of falling water to generate electricity. The concept is called pumped-storage hydro. “In the long run, the renewable piece will be one of the largest in the West,” he says.

READ — Taming Agriculture’s Energy Hogs

Colorado has very few pumped-storage hydro projects. The largest is Cabin Creek, near Georgetown. Water is pumped from a reservoir along the road to Guanella Pass at night when electricity generally is most available and at the lowest cost, then released to flow downhill and generate electricity when needed to meet peak demands. The total capacity is 324 megawatts, equal to a modest-sized coal-burning power plant. As they stretch to accommodate higher and higher quantities of emissions-free but intermittent renewable generation, electrical utilities will need more storage. Pumped-storage hydro is one option. Several sites have been identified in the Grand Junction, Craig and Hayden areas.

The Green River water, once arrived in the northern Front Range, would have other purposes, too. Million reports interest in up to 400,000 acre-feet. This interest reflects the rapid population growth. Places that were small towns a half-century ago — think Timnath and Berthoud, Windsor and Johnston, Erie and Lafayette – have in some cases become small cities. “This region is a job-generating factory, and that is what is bringing people here,” says Jeff Stahla, public information officer for Northern Water.

Northern Water operates Colorado’s largest transmountain diversion. The project diverts an average 261,000 acre-feet annually from the Colorado River at Grand Lake through the Alva Adams Tunnel to the Estes Valley. From there, the water is distributed across Northern’s service territory from Broomfield to Wellington and along the South Platte River to Julesburg. In 1957, when the federally financed work was completed, the Colorado-Big Thompson project delivered 97% of the water to agriculture. Today, it’s roughly 50%.

Prices for Colorado-Big Thompson water have been rising rapidly. A chart assembled by Northern Water shows shares in 2012 selling for a little more than $7,000. This summer, Lafayette paid $70,000. That’s roughly $100,000 an acre-foot. Eyebrows were raised. Thornton and Aurora, meanwhile, plan to import water from the Fort Collins-Greeley area. The cities began securing those agricultural water rights decades ago.

These numbers bolster Million’s case for revenues. His new backer is the largest pipeline company in North America, he says. “They know their business. They know their costs.” Those costs come in at $2.5 billion, he reports, compared to $5 billion in potential revenues.

But can water be had from the Green River? Million insists there are no major obstacles. Most challenging in the permitting process will be securing the right to cross federal lands, he says. This is despite the proposed pipeline paralleling many other pipelines, although the others have been laid for fossil fuels.

More troublesome yet may be getting a permit from Utah to divert from the Green. The state has denied the application by Water Horse Resources. Million argues that the 1948 Upper Colorado River Compact accommodates diversions by one state from another within the Colorado River Basin. That is why Santa Fe and Albuquerque can divert water from the San Juan River near Pagosa Springs before that water flows into New Mexico. The Green River flows into Colorado for 40 miles on its way to join the Colorado River near Moab.

Million is an outsized, colorful character. He seems to have no fear. You can imagine him picking up a rattlesnake. He has, he confirms, and in fact had a pet rattlesnake while an elementary school student then living near Trinidad. He was schooled mostly in Boulder but spent his summers and a year or two of primary school living on a family ranch along the Green River near the eponymously named town in Utah.

His explanations are littered with cows, horses and hats. For example, in reviewing his long-dormant journey with this idea, he reports an evolving detachment. “When you let go of the reins of a horse, sometimes it has a tendency to find its own trail. And I think we’ve done that here,” he says of the new energy-focused plans.

That horse has been steered by the massive game-changer of the warming climate. The risks predicted decades ago are being realized. This has driven the enormous push to shift to renewables, creating new business opportunities, including the potential for new pumped-storage hydro plans.

Climate change has also exacerbated the long-festering problems in the Colorado River Basin. The interstate compact adopted 100 years ago November by the seven basin states assumed roughly 20 million acre-feet of river flows. In this century they have averaged 12.5 million acre-feet. The river ceased to reach the Pacific Ocean in the 1990s except in one artificial discharge from dams. If climate models are accurate – and they have now been validated by time – the water situation will worsen.

This sounds grim. Actually, it’s worse. Approximately 25% of the river flows are apportioned to 22 federally recognized tribes in the Colorado River Basin. The tribes have only partially claimed them. They are, however, senior to all others — including the diversions by cities along Colorado’s Front Range. This cart has been upset, apples everywhere.

Droughts do come and go. But when drought departs, the warming climate will remain. A 2017 study, for example, found roughly half the drying now observed in the Colorado River Basin was the result of human-caused global warming. Other studies have come to similar conclusions.

Might the warming climate actually deliver more snow or at least rain? That’s possible. Climate models 15 years ago suggested the San Juan Mountains would become drier, and they have become so. The San Juan River that flows through Pagosa Springs has had a 30% reduction.

Colorado’s northern mountains might actually get more snow or at least rain. Million pins part of his argument on a wetter future roughly north of Interstate 70. Jeff Lukas, a water and climate consultant from Lafayette who co-authored a book about climate change impacts, says Million is not entirely wrong. “But it’s not a free pass out of climate change,” he adds. Even if the Green River in Wyoming does get more snow and rain, that gain may be more than offset by increased evaporation.

The upper Green River – the portion in Wyoming, upstream from Million’s proposed diversion – has had 17% less precipitation in the 21st century than before. A 2022 study by researchers from Los Alamos National Laboratory and other institutions found that “the Green River Valley area may experience large drought pressures from increasing aridity combined with changes in the seasonality of runoff contribution to streamflow and snowmelt upstream.”

So, will there be water to divert? Million argues yes. He points out that Colorado and the other upper-basin states have not been taking their share of water apportioned under the Colorado River Compact. That’s the position of Colorado and other upper-basin states. In this view, it’s time for California and Arizona to get their houses into order, as they have been the principal reasons for the decline of the two big reservoirs, Mead and Powell.

Million contends the 1948 Upper Colorado River Compact clearly allows Colorado the diversions, even if from Utah. After all, New Mexico diverts water from the San Juan River near Pagosa Springs, before that river enters New Mexico. It’s analogous to what Million and Water Horse Resources want to do, but from an entirely different era. It was completed in 1976.

Many in Colorado’s water establishment – which Million clearly is not – fret that an additional diversion, particularly of the size of Million’s pipeline, will put Colorado close to dangerous edges. “Particularly when there are no customers for the project,” says Peter Fleming, the general counsel for the Colorado River District, a Glenwood Springs-based organization that represents most of Colorado’s Western Slope.

That’s an ultra-touchy subject. Colorado water law does not allow speculation. Water has to be used or the right to it is lost. Million says he has interest from 17 different users. He has not, however, identified them.

But even if the lower-basin states have been using more than their share, there’s also the issue – which I first wrote about for ColoradoBiz in 2009 in a story called “Tapped Out – about whether Colorado might risk being forced to curtail diversions from the Colorado River. This is because of a provision in the 1922 compact that says the upper basin states cannot cause less water than 7.5 million acre-feet to flow past Lee Ferry (near the Grand Canyon) on a rolling 10-year average.

That messy situation, both legal and political, is one reason the South Metro Water Supply Association pulled back from a parallel plan to Million’s. The Greenwood Village-based organization – which includes Castle Rock, Parker and 12 other water providers — had created the plans after Million first outlined the vision. It was called the Colorado-Wyoming Coalition, and it had organizations from both states. That interest has waned, at least among South Metro members.

“Complications with a Flaming Gorge project, given the cost, needed infrastructure and the myriad of issues involving the Colorado River (which, as we know, conditions of which have worsened significantly in recent years) certainly served to shift attention to other projects,” says Lisa Darling, executive director. “For example, one of my members, Parker Water, has been working with agricultural interests and other partners on the lower South Platte on a project called the Platte Valley Water Partnership, an innovative water project that will provide sustainable water supplies and support continued ag production.”

What exactly the Fortune 500 company brings to the table, that’s not clear. Million says the agreement is confidential, but he does say MasTec will have a construction stake and also be a customer for the water. The company has constructed a 51-megawatt wind farm near Burlington and a solar project in Douglas County.

On the face of it, this looks to be a high-risk but potentially high-reward project. Million says that’s backward. “The fact that we’ve landed a Fortune 500 publicly traded company would reflect the opposite,” he says. “Publicly traded companies don’t enter into investments with high risk. They’ve done their homework.”

As for Million’s quest, he reports devoting six or seven years in the past two decades to this quest but also says he has been involved in other things. But he does acknowledge the perception of a Sisyphean undertaking. He tells about riding an elevator in Fort Collins with an attorney who called out to him. “So you’re the Walt Disney of water,” she said.

Disney, notes Million, was rejected 300 times by bankers with his vision of Mickey Mouse and a park.

Allen Best has been writing about Colorado water steadily for the last 20 years for ColoradoBiz, Headwaters magazine and now for his own publication, Big Pivots.