What you should know about cybersecurity in the upcoming election

Thanks to emerging technologies, no election is safe

Alicita Rodriguez //March 2, 2020//

What you should know about cybersecurity in the upcoming election

Thanks to emerging technologies, no election is safe

Alicita Rodriguez //March 2, 2020//

If you were feeling confident that the United States government and its states’ governments were prepared for the 2020 presidential elections, then the Iowa caucus on Feb. 3, 2020 might have upset your sense of ease. Thanks to a new app commissioned by the Iowa Democratic Party, the midwestern state’s results were unexpectedly delayed. Their election problems stemmed from the one area we need to focus more on — technology.

Should we be worried?

Yes, according to Joseph Murdock, an instructor who teaches information systems in the CU Denver Business School. “Prior to computers, if I was going to manipulate your vote, I would need some type of proximity,” Murdock says. This is no longer true.

Murdock is currently developing a master’s program in cybersecurity at CU Denver, after previously establishing a Cyberdefense program recognized by the National Security Administration (NSA) and the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) at Red Rocks Community College. Part of the problem is that the United States is seriously understaffed.

“We don’t have the talent for cybersecurity jobs. We graduate about 10,000 students a year nationwide, when we need to fill around 400,000 jobs in the U.S. alone,” Murdock says.

Blame the internet

The biggest problem with cybersecurity comes from computers and other devices being connected to the internet. “When you connect to the internet, somebody halfway around the world can try to attack your computer or access your system — and you wouldn’t necessarily know it,” Murdock says.

Countries and states with the safest election processes use secured computing environments with paper backups. “Colorado is a leading state for voting security,” Murdock says. “Colorado is a model for the country.”

If states do use computers, voting machines or apps, they should ensure that they are configured properly, securely and operating on secured networks. Of course, the election process is safer if you maintain a paper copy for records and auditing of votes, which is why more states are using paper ballots instead of, or along with, direct recording electronic (DRE) systems.

But you don’t need to directly manipulate the voting process to interfere with elections. “If you look at the 2016 presidential election, it was influenced by foreign actors but not necessarily through compromising voting machines,” Murdock says. Voters were manipulated socially — through Facebook ads, social media posts, disinformation and deepfakes.

Most computers have the capability to create deepfakes

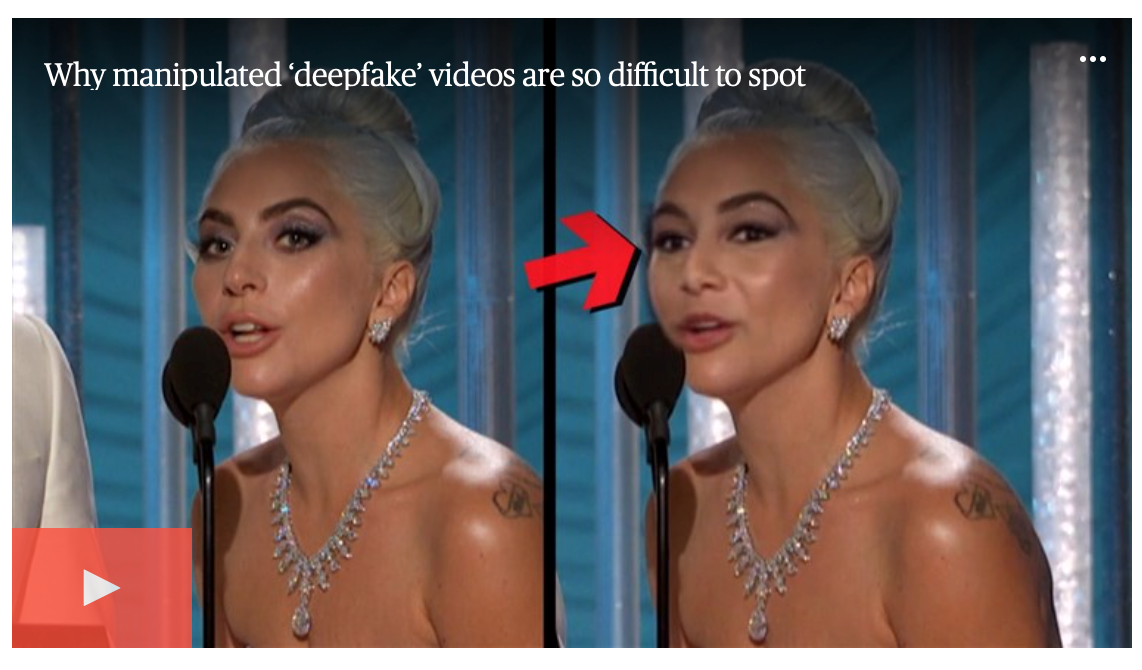

The term deepfake combines deep, which refers to deep learning, and fake. “A deepfake is manipulated video that a computer has generated autonomously using machine learning,” says Jeff Smith, the associate director of the National Center for Media Forensics (NCMF) in the CU Denver College of Arts & Media.

He is involved in the production of deepfakes as part of NCMF’s research. The NCMF is creating deepfakes in order to understand how to identify and expose them.

Recently, Smith used his research lab to create a deepfake that aired on the TODAY show. The video face-swapped Lady Gaga with NBC’s Morgan Radford, illustrating how potentially dangerous the technology can be. Deepfakes pose a bigger threat to people in the public eye, like celebrities and politicians, because videos of them are readily available for anyone to manipulate.

“Victimization can be carried out in different ways,” Smith says. “Making someone look as if they’re doing or saying something that they didn’t.”

It’s not particularly hard to create a deepfake. “In terms of technology, most people have the capability with their current computer,” Smith says. The hurdle is in the programming.

“It’s not easy to get the Python-based programs up and running,” he says. “Not only does the software require proficiency in programming, but to create a convincing deepfake capable of disrupting an election, it will take a team of people working together to cover other aspects such as the video production, the voiceover, and social media engineering to make it go viral.”

Social engineering, disinformation and propaganda

Both Murdock and Smith agree that the upcoming election will likely be manipulated using technology. “Traditional actors have teams dedicated to this,” Murdock says. “The U.S. government does it, the Russians do it, the Chinese do it. Propaganda has been around for a long time, but computers make it easier to reach larger audiences.”

When asked if disinformation will be aimed at disrupting the 2020 U.S. voting process, Smith said, “Definitely. But I’m not certain if we’ll see that carried out with deepfakes as much as we’ll see more easily executed forms of disinformation like photoshopped images or image recontextualization.”

The real problem may not be sophisticated cyber-interference or convincing deepfakes. What Smith calls disinformation, Murdock calls social engineering, which, when used over the internet, technically falls under cybersecurity.

“The Russians are fully capable of creating disinformation to affect our elections without deepfakes,” Smith says. Furthermore, once lies are spread, it’s not easy to counter them. Given that the human brain can’t unsee or unhear what it has already processed, “It’s possible that psychologically the damage is already done,” he says.

Any interference in the upcoming 2020 election will likely target people in the middle of the political spectrum, which means anyone who is not in one definitive political party should be especially cautious. Murdock tells his students to question everything. “We can have our own opinions, but we shouldn’t be able to have our own facts,” he says.

Alicita Rodriguez is a senior writer for the University of Colorado Denver. She holds a BA in English Literature from Florida International University, an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University and a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Denver. This article can be attributed to City Stories, a publication by the University of Colorado Denver.

Alicita Rodriguez is a senior writer for the University of Colorado Denver. She holds a BA in English Literature from Florida International University, an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University and a PhD in Creative Writing from the University of Denver. This article can be attributed to City Stories, a publication by the University of Colorado Denver.