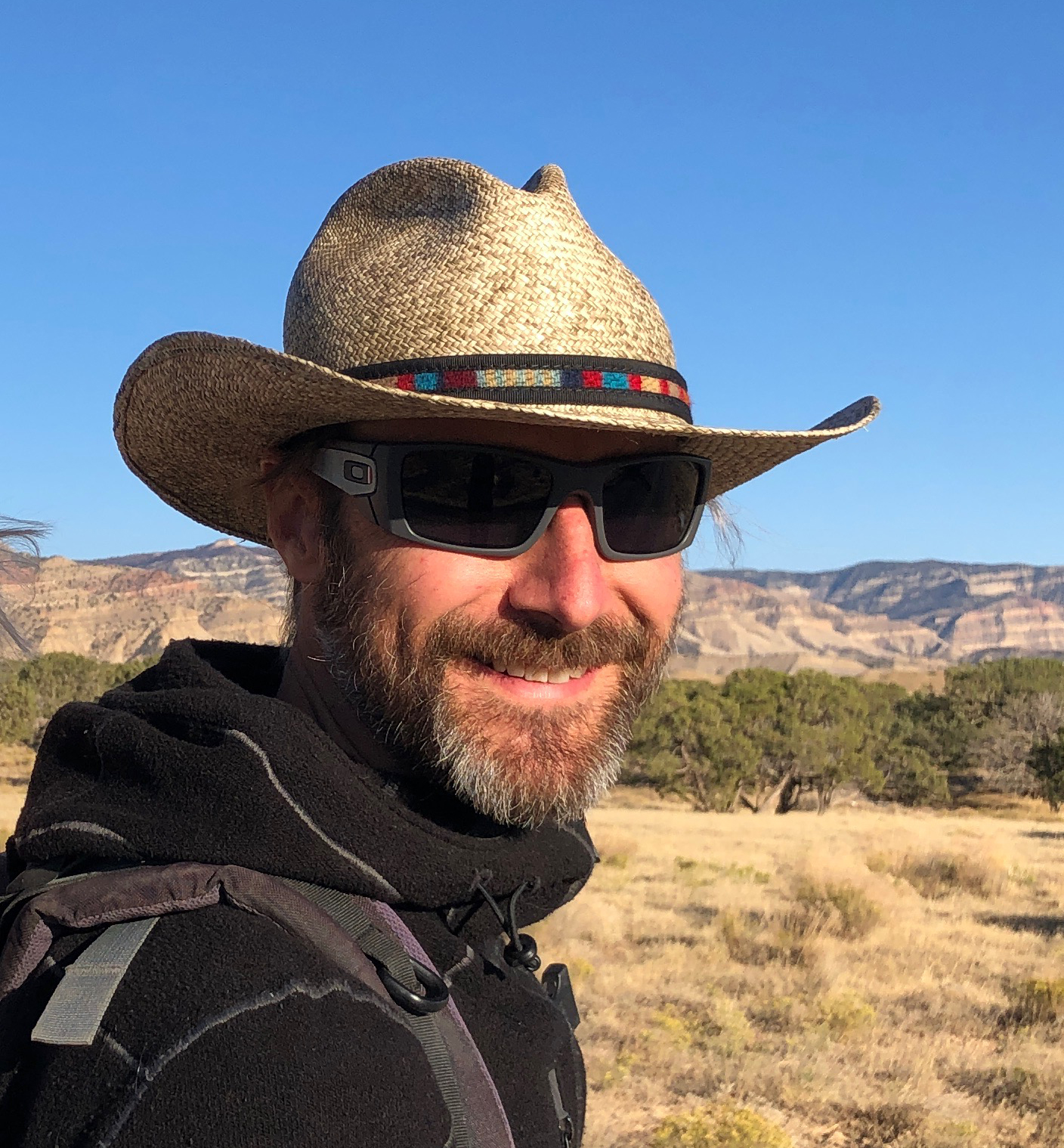

Nordmark co-founded eBags in 1998 and served as CEO through 2008 and chairman until Samsonite acquired the company in 2017.

The company was profitable in 2001 and not only survived the dot-bomb, but thrived to the tune of 29 million bags sold before the acquisition.

For his follow-up act, Nordmark moved into software and artificial intelligence (AI) with Iterate.ai in 2013. Now with a little more than 100 employees in Colorado, California, India and Sri Lanka, the company is rewriting the book on software development for such customers as Maaco, Jockey, Ulta Beauty and Circle K.

Age: 61

Hometown: Westminster

What audiobook he’s listening to: “In Order to Live,” by Yeonmi Park with Maryanne Vollers

ColoradoBiz: How did you transition from eBags to Iterate.ai?

Jon Nordmark: When I was with eBags, I worked with a lot of software companies, and I thought, “If I ever start another company, I want to do a software company.” And then I met my work partner, Brian Sathianathan, in Kyiv, Ukraine, and we were on a board of directors of what is like a Techstars of Eastern Europe. And he’s a software guy, so it was meeting the right co-founder that was the catalyst to getting this going. We worked together over there between 2011 and 2013, and it was in 2013 when we said, “Hey, let’s do this together.”

CB: It looks like Iterate.ai has evolved quite a bit since 2013. Can you tell me a little bit about where it started and where it is now?

JN: The initial premise was, we wanted to help large organizations innovate faster and more economically, basically faster and cheaper. And at the time, we thought the way to do that was to tap into startups from all over the world. What we realized in Kyiv was that startups didn’t need a lot of money to start anymore because the cloud had been invented by Amazon, basically, AWS, because of open-source code that was available.

These companies that we were seeing in Eastern Europe were launching without any money; they just tried to pay really tiny server fees to Amazon, and all the code was free, the starter code, from code libraries that were open sourced, and they didn’t need to buy servers. Back in the eBags days, we had to pay like $50,000 a server. A normal person could not just go start a company. It was just way too expensive.

What Brian and I realized was the barrier to starting a company had shifted from capital, or money, to brains. And it was all those smart people in Eastern Europe launching companies with no money in the Techstars of Eastern Europe, so what we wanted to do was connect large organizations to those little startups. But then we realized large organizations have trouble integrating these startups. They just don’t have the infrastructure, all their existing tech stacks weren’t prepared to do that, so that’s why we ended up building what’s called a low-code development platform, which makes software development really easy and fast to do.

Then we just started building our own applications that big companies can buy. In 2017, we changed our name from Iterate.com to Iterate.ai. The reason was, one of our employees has a Ph.D. in artificial intelligence, so we were getting asked to do a lot of AI work a longtime ago. That’s why we became an .ai company, because we could do stuff that no one else seemed to really be able to do. And because we’re getting asked for so much of it by the time 2017 came, we just changed our name to Iterate.ai. Since then, that’s what we’ve been focused on, but it wasn’t until November 30, 2022, when ChatGPT launched that the whole world started looking at AI. We happened to be in the right place at the right time by accident, to some extent.

CB: How has the business changed since ChatGPT launched?

JN: Everything we do now seems to have an AI focus, whereas before maybe it was 70 or 80percent. We also shifted into building a lot of generative AI capabilities for many companies. We’ve built probably 15 large language models [LLMs] that operate in private environments for big organizations. It shifted our work. We’re still doing AI, but it has become a lot of generative AI work.

CB: How are your customers using these LLMs?

JN: We built one to help actuaries at a big insurance company. We built one to manage social media interactions with 15-year-old girls for a big cosmetics company. And it speaks in emojis and stuff like that.

Those are two examples of completely different use cases. One is actuarial, which is heavy-duty math, and it actually is a combination of technologies. It’s not just an LLM; we’ve got some math capabilities we built into that, that are not out of the large language model. It’s kind of a combination.

Then you have the social for the girls that is all emojis, the opposite. But they both have their own unique language. Then we built a bot that schedules really expensive parties. We built one for ourselves that writes AI software. So think of generative AI code that writes AI code in Python. We built that, and that actually works really, really well.

We’ve done a number of what we call executive bots. Let’s say you’re a CFO and you need to talk to the financial community. You can jus task questions to this bot that goes and pulls all this really private information out of their system, and gives you answers on the fly in a human way. It not only uses a large language model to put answers in plain English, it also accesses customer information, financial information, market research information, and it combines a lot of private information with the public LLM.

But it’s all kept in a private environment so no information is leaked onto the web.

CB: Are you still utilizing the low-code development platform?

JN: It’s all been developed in that low-code platform and operates on it.

That low-code platform also operates in production. At CES (Consumer Electronics Show), we presented two keynotes with Intel. The reason they chose us was because our engineers figured out how to process these large language models on CPUs [central processing units] instead of GPUs [graphics processing units]. Nvidia has become a trillion-dollar company because they created these chips, which are called GPUs, that process AI.

They really were started to do gaming — it’s intense processing — but it just so happened that they kind of got lucky that they can process AI on those gaming chips.

Intel then got left in the dust because they weren’t prepared so much for the AI when it came out. But now they’ve been adjusting their chips a little bit. They sell what’s called a CPU, central processing unit, and we have helped them be able to process AI on their CPU chips, just like you’d process on a GPU. It’s a lot cheaper for a big organization to use a CPU versus a GPU, and it’s also cheaper to buy a CPU than a GPU.

So we’re making these large language models and generative AI capabilities accessible in a super much more cost-effective way for normal organizations.

CB: Does every business need to be looking at AI and jumping in now?

JN: Yeah, we think pretty much every company needs to use AI.

You can look at it from the highest level. I think America has to be in a leadership position. Right now, we are because of our big tech. We’ve got Microsoft and Google and Facebook and Apple, they’re all leading the charge on this, then you’ve got some really strong startups that are big like OpenAI and Anthropic involved, and then you’ve got ones like ours that are just incredibly scrappy.

Europe doesn’t have any of those companies, almost none. They’ve got a couple, but not many, so it appears they’re going to get left behind. Asia is behind us because they don’t have the chip processing power and America won’t send it to them — they’re banning Intel and Nvidia and those companies from sending powerful chips to China.

I think, from a country perspective, you have to stay in front, and we’re doing that, but then from a company perspective, it’s the same thing. Companies that get involved quickly will get efficiencies. They’ll just be able to outpace competitors that don’t move with it.

There’s a saying: AI won’t take your job, but a person who knows AI will take the job of a person who doesn’t.

CB: You mentioned that you’d developed AI to write AI code. Are you currently using that tool?

JN: We’re using it to develop snippets of code. But the thought is that as time goes by, that tool will get better and better. Right now, you can only generate small snippets of code. As time goes on, it’ll be able to ingest more and produce more and just be more accurate as it gets more feedback. If companies can produce the way we think we’ll be able to produce, other companies will just have to keep up.

CB: What has the company’s growth curve looked like since 2022?

JN: We’ve raised very little money on the whole, like $3 million, but our revenues are north of $10million, a fair amount north of that. And we’re always growing nicely into the double digits; we probably average 35 percent each year, somewhere in there, so it’s not super-high growth, but it’s certainly good growth.

CB: What do you think will be the big AI story of 2024?

JN: One that we’re all anticipating is the release of ChatGPT 5. What’s that going to do? Because when we went from 3.5 to 4, that was a pretty big move.

I’m also waiting to see what the open-source community does alongside Facebook or whatever you want to call them, because Facebook is sort of leading the charge on continuously releasing open-source models that then the whole world can go in and innovate on. I think that’s really pushed the envelope.

If you think of AI, there are four types, at least in our mind. The first one is classification AI. It’s just analytics, being able to evaluate numbers, and stuff like that. That was the first type of AI, just being able to classify things.

The second type of AI is generative AI, where all of a sudden, it can create images or create a research paper for a high school kid, so it almost seems like it’s creative.

Instead of just analyzing data, the third AI is going to be what we call interactive AI. That’s where autonomous agents come in and start acting on your behalf. Another thing that we’re working on right now is an interactive AI where you can actually do a drive-thru and all the order processing and order taking is done with a computer, and it talks to you like a human. We built that already.

The fourth one is artificial general intelligence, which is probably quite a bit further out. But we’re entering that third stage right now, and that will begin to be visible this year. And we know that because we’re building it.